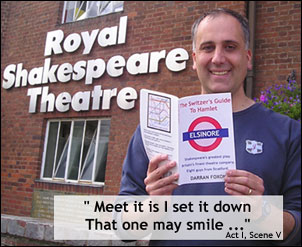

The Switzer's Guide To Hamlet

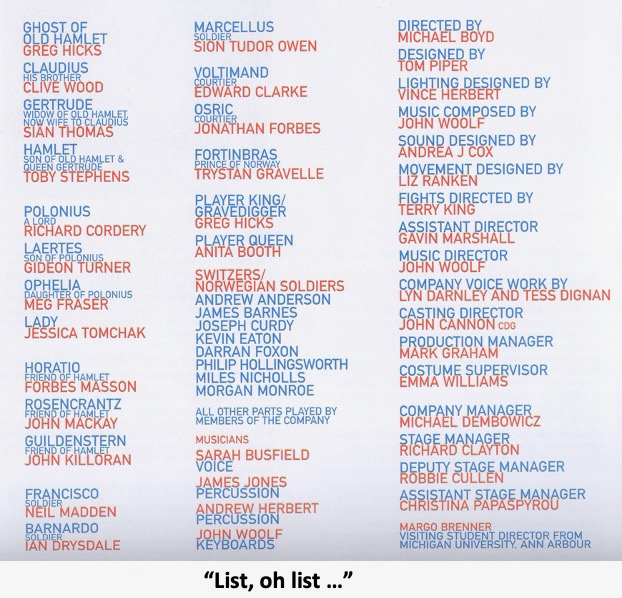

In 2003, Michael Boyd was appointed as the Artistic Director of the Royal Shakespeare Company. His ambition and desire was to re-establish it as a leading theatrical company. In his first summer season, Mr Boyd directed "Hamlet". He chose to cast some of the stage's leading Shakespearian actors: Toby Stephens in the title role, Sian Thomas as Queen Gertrude, Clive Wood as King Claudius and Greg Hicks as the Ghost of Hamlet’s murdered father. He also chose to include a group of extras in the company. The extras were not actors; they were eight Stratford residents who responded to an advert placed in the local paper.

This however is the story of the Switzers who gained less attention – indeed only a one line reference in "The Guardian" review marks their contribution - but the Switzers saw close-up the hard work and sense of fun that goes into the production of a play.

"The Switzer's Guide To Hamlet" tells the story of eight ordinary people in what was to become an extraordinary production. It gives a scene-by-scene insight into the thrill of standing on the Royal Shakespeare Theatre stage in Stratford and watching close-up as the performance develops.

The Switzer's Guide to Hamlet

A drum beats, the Court comes in, we all stand to attention.

The King speaks, we stand at ease so lowering the tension.

The King is somewhat puzzled, he says “Hamlet why so glum?

Alright, I know your Dad's died, and O.K., I've married Mum.

Don't be a party-pooper and towards us don't be cool.

Why not stay in Elsinore? Forget about that School.”

The King is keeping busy as people start to call.

We stand watching over him, backstage beside the wall.

Ros.& Guil. report to the King, as we stand by the door.

We go off in separate ways, as the Players take the floor.

Hamlet taunts Ophelia, he says he wants to shag her.

The play stops, it all “kicks-off”, the Prince whips out his dagger.

The temperature is rising, the King talks of fear and rage.

We walk left, right and centre swiftly across the stage.

The Prince is under pressure, though not quite “on-the-lam” yet.

A search-party enters and goes chasing after Hamlet.

The King asks “Where's the body?” Hamlet is loath to tell him.

We're told “Go search the lobby, quickly before you smell him.”

Fortinbras makes his entrance, back-lit none can see your face.

Though make sure in the tea-break, your helmet is in place.

“Who's for King Laertes?” the blooded, unruly mob roar.

As we walk shouting to the stage, then hang around by the door.

The funeral party enter, walking slowly in a column.

Her brother gets a bit upset, wants it to be more solemn.

The Queen lays down her flowers, Ophelia is interred.

Hamlet fights Laertes whilst Horatio is deterred.

The Prince has gone and torn it, he's really made a scene.

The King now wants him followed. So go off before the Queen.

Hamlet (dying) kills the King, who tried so hard to “top him.”

We walk on stage, pick up the Prince, for God's sake do not drop him!

The final scene, a costume change, now a Norwegian soldier;

stand smartly in the door-way, a cross-bow on your shoulder.

The play is done and dusted, and we made it with some luck.

So go enjoy the curtain-call, then go down the “Dirty Duck”.

“Is this a prologue, or the posy of a ring?”

The article had asked for a photograph. The only full length one I had to hand was of me carrying our baby daughter in a sling – hardly the image of a medieval hard-case but it would have to do. I sent it with a covering letter and three weeks later I received a phone call asking me to join the other applicants at the Royal Shakespeare Theatre for a briefing with Mr Michael Boyd, the Director. Eight other Stratford residents had answered the Company’s call to arms. We chatted nervously as we waited for Mr Boyd to greet us. We knew this was not an audition. We knew that the Company just wanted reliable people that would turn-up when requested. But this was the most famous theatre company in the world, performing arguably Shakespeare’s greatest play in one of the Britain’s best-known theatres. No-one wanted to miss out on this opportunity. Mr Boyd walked into the room and looked at the eight of us. I was immediately reminded of the England cricket captain’s comment when he learnt of the selector’s choice of players: “My God, what have they sent me!” Indeed Mr Boyd’s first reaction was to step out onto the balcony for a restorative cigarette (though we hoped this was more of a reaction to a hard day in the rehearsal room). I wrote “The Switzer’s Guide To Hamlet” originally as a verse to remind me of the stage directions. A friend pointed out kindly that it “ ain't iambic pentameter”. In fact, it is three syllables per line short of the regulation ten. I resisted the temptation to tell him that the inspiration for this seven-syllable structure was actually the Seventies pop song “Cool for Cats” by Squeeze.

The “Guide” only mentions the scenes that the Switzers were in. It is rather like the shepherd-playing schoolgirl who tells her parents that the Nativity play “is about some shepherds that visit a baby”. Despite being in twenty performances of the production, I regret that I never actually saw the whole play – only bits of it. This was a vertical-tasting across a Stratford summer. Different aspects came to the fore as our run developed. After a spell of sunny weather the Elsinore court showed the benefit of a healthy tan. On other occasions, cast members would give upbeat performances when their partners or family were watching.

The Ashcroft Room is spacious and well lit with a fantastic view over the adjacent River Avon and surrounding Stratford parkland. A mock-up of the stage set has been built and tape is laid on the floor markingout the entrances. The cast have been resident for sometime as they work towards the opening night. We, the Switzers, sit to one side on a bank of chairs watching the action. It is fascinating to observe the cast at work. At one point, Mr Boyd holds and strokes Toby Stephen's hand as he gives his notes on the scene. This is a curiously intimate action in a room full of people but goes un-remarked. I notice that most of the actors hold to the dictum "don't stand when you can sit, don't sit when you can lie down". At any stage, several are lying on the floor. As another food poisoning stomach-cramp runs through me I decide that it might be an idea to lie-down before I fall out of the chair. I gently slide to the floor and hold my stomach as though I'm doing some deep Pilates exercises. My fellow Switzers look at me as though I’m mad but at least I no longer feel like throwing-up. Toby Stephens is to play Hamlet. He is the son of Dame Maggie Smith and the actor Sir Robert Stephens. I searched for his name in "Google" and I read that he is part of the “aristocracy of British Theatre". He is a good-looking, well-spoken man with a very strong presence. In short, he has all the attributes to be extremely intimidating. Our first rehearsal scene with him, ironically, is actually the last act of the play. Four of us are to carry his dead body on our shoulders off the stage. We are to lift him as one from the prone position. This would be intimidating in any circumstance, but to carry that season’s hopes of the Royal Shakespeare Company on our collective shoulders adds to our tension. We approach his body nervously, one Switzer positioned at each of his limbs. On the order to lift, we bend and place his arms around our necks.

After a day of intense rehearsal, Mr Stephen’s deodorant has finally broken down with huge damp patches around both his arm-pits. There is a distinct whiff of the “aristocracy of British Theatre". As one the five of us break-out in laughter: "sorry guys" says Toby and the ice is broken. We break for a supper in the Green Room. This is a small cafeteria at the back of the theatre. It serves light snacks and more importantly refreshing cups of tea and flapjacks. The walls are adorned with the hand-prints of previous RSC actors and their respective productions. As this is England, smokers are “doomed for a certain time” and are required to stand on the balcony overlooking the River Avon. There is only one perk of being a Switzer; a five pound food allowance per show. Suffice to say, we make the most of it. Afterwards back in the Ashcroft room, a football is produced and a knock-about game of "keepy-uppy" (also known as “Hacky Sack”) commences. King Claudius proves that he can juggle both the demands of State and a football. At about nine-thirty our Rehearsal ends. From now on we do it for real.

"A drum beats, the Court comes in, we all stand to attention.

The King speaks, we stand at-ease so lowering the tension."

The Company Manager gives a Health & Safety talk. He walks to the front of the stage to illustrate a point, as he does the front of the stage dips alarmingly under his weight. A member of the cast turns to me and says “Jesus, that’s going to be fun to walk on”. I nod and grunt agreement with him sagely as if I know what I’m on about.

The King is somewhat puzzled, he says “Hamlet, why so glum?

Alright, I know your Dad’s died, and O.K., I’ve married Mum.”

"Don’t be a party-pooper and towards us don’t be cool.

Why not stay in Elsinore? Forget about that School”

I wander back to the counter for a fresh cup of tea and as I go I hear Clive muttering under his breath: “echoing?” This is the Switzer’s first scene and after that we have forty minutes to fill before we are called back again The King is keeping busy as people start to call. We stand watching over him, backstage beside the wall We are in the Green Room. The sound on the two stage monitors is turned-down and every attention is given to the 2004 Summer Olympics on the T.V. It is the final of the 4x100 relay. All eyes are glued to the screen ready for the gun to be fired. A cast member glances at the action on stage. “Aren’t you in this scene” he asks his colleague next to him. His table companion rushes to the door and heads frantically towards the stage. “A new event – the Hamlet 25-yard dash” he mutters as he turns back to the athletics.

“Has he jumped yet?” the tall figure gazes at the stage monitor. The black and white figures hard to distinguish on a fuzzy screen. We have a long wait before we go back on stage. Hamlet must meet the ghost of his Father, learn of the murder and then swear revenge before we return. We hang out in the Green Room sipping cups of tea and eating flapjack. On stage, the Ghost will fall back into the stage through a hidden trap-door. Greg Hicks, holding his body sword-rigid, will bravely tumble into his grave and back to Purgatory. Meanwhile, we enjoy the summer’s evening on the Green Room balcony overlooking the river. Above us on the first floor are the main dressing-rooms for the key characters. Occasionally, tourists walking by are treated to the sight of Queen Gertrude using her mobile phone. I had walked back to the dressing room to pick-up my forgotten helmet. The building corridors have the smell and colour of a run-down old school. Piles of old costumes, boxes of leaflets and posters turn the walk into an obstacle course. The Queen is now walking slowly towards me. With her ornate costume, there is no room for the two of us to pass. I stand in the doorway as she passes. “Thanks” she says gratefully “This costume is like moving about with a large sofa strapped to your back” I stand on the balcony talking to Osric. Every time I see him he is wearing a different hat and I am puzzled about this. He plays several characters in the play (as do others). He explains that the hats are apparently to help the audience distinguish between his characters. I reflect inwardly on an actor’s life: five hard years of Drama School, the thrill of being cast by the Royal Shakespeare Company in a main-stage production and then the good news: “oh wear different hats so that the audience know who you are playing.” Still, he seems to take it in good spirit. We are joined by the King who has slipped on to the balcony for an inter-scene cigarette. He and Osric swap insulting banter. I switch into Switzer-mode and manage to catch the King’s eye. “Do you want us to sort him out?” Osric looks appalled: “Jesus, you sound like you mean it.” Stratford is a major tourist centre. Opposite the Theatre and across the River Avon, several holiday boats are moored-up. We can vaguely see a naked figure through the frosted port-hole of one of them. The actors have become the audience as we watch the figure soaping itself. Several Switzer fantasies are put forward about the charms of this half-obscured figure. It’s a good way to waste five minutes though of course when the shower occupant eventually walks on deck, he is an old, grey-haired gentleman. Still, we wait for our call to action. We look back at the monitor, waiting for Greg Hicks to wail for his revenge. “Go on you bugger, jump!” we shout at the Ghost.

“Ros. & Guil. report to the King, as we stand by the door.

We go off in separate ways, as the Players take the floor.

We are walking back-stage towards our places for the next act. Above our heads, two black & white T.V. monitors show the action on each stage. One is for the main theatre and the other for the adjacent Swan auditorium. I stand next to Queen Gertrude as we watch the action next-door. The RSC are showing a season of Spanish plays – imaginatively called the “Spanish Season”. The plays all have lavish costumes and frequent, energetic scene changes. "Oh, their play does look a lot of fun" comments Gertrude almost enviously. I agree with the Queen. When compared to three hours of heavy-weight political intrigue, "Pedro, The Great Pretender" is welcome light relief. I notice a pair of boots at one of the change stations. They are made of engraved leather, with pompoms and spurs. I offer to wear them in the next scene to "liven things up". On reflection, we agree that this wouldn't be a good idea. There are three Switzers in this scene. Two stand guarding the back of the stage and one is to escort Rosencrantz and Guildenstern down the parados from the back of the auditorium. The actors playing the pair are young and fit – a critic comments that one has “spectacularly funny long legs“. The duo sprint down

the parados effortlessly. They are followed by an outof- breath Switzer struggling to keep-up. On stage, the escorting Switzer is to show the pair offstage when they are dismissed by the King. My understanding is that the Switzer signals with his arms and shepherds the duo off, following behind them. Not for the last time, my understanding is wrong. Neil Madden, a member of the cast and the Switzer leader, nods his head to me and I point off-stage with my left arm. No-one moves. Neil looks at me, points with his arm off-stage. No-one moves. I look at Neil, and sweep my right arm towards the exit. No-one moves. Neil looks at me imploringly and sweeps his other arm towards the exit. No-one moves. We seem to be communicating in semaphore and any navy personnel in the audience will probably think the message is coming through to “sink the Bismarck”. Suddenly, the penny-drops and I then walk off-stage and people thankfully follow. The direction for the other two Switzers guarding the door at the rear of the stage is to walk off separately: only one is to escort the King and Queen down the parados. This evening, I am supposed to exit through the back of the stage though my wife is in the audience. Without telling anyone, I decide to join the Royal group as they walk down the parados. It will give me a chance to wave to my wife as I go by.

I march down the walk-way and manage to catch Regan’s eye. As we reach the back of the seats though the theatre door is slammed in my face. I am trapped inside. Feeling like a low-budget Black-Rod I tap on the door. It is opened by Ophelia. “Sorry” she says letting me through “I thought that was everyone”. It is a just comeuppance for me daring to offend the Gods of Theatre! As I make my way back to the Green Room, I bump into Mr Boyd who is watching the action from the wings – I ask him how he thinks it is going. “It’s thickening nicely” he says making the whole enterprise sound like a bit of Shakespearian sauce.

Hamlet taunts Ophelia, he says he wants to shag her.

The play stops - it all “kicks-off”- the Prince whips out his dagger

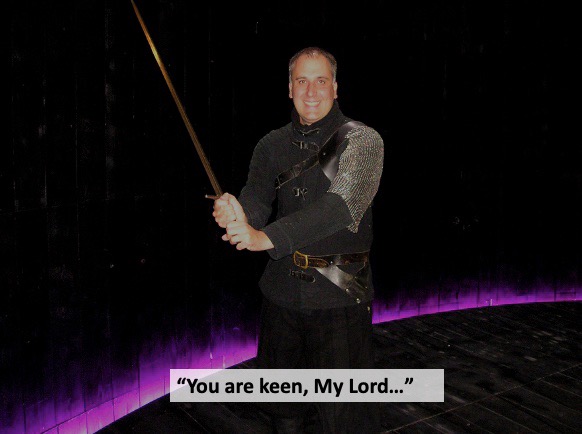

In our rehearsal, Toby Stephens delivered the “to be or not to be” speech in the middle of this scene just after the King had risen to stop the Players. This famous monologue muses on the attraction of suicide and is normally delivered earlier in the play. When delivered in this scene, it has a far greater impact. Hamlet believes that he has tricked the King into revealing how his father was murdered. The King has responded by calling for his Switzers to protect him. The tension is extreme. It seems that the each has broken cover and now the death of one of them is the only resolution. I’m reminded of Michael Collins’ comment: "I tell you, I have signed my own death warrant." It is powerful theatre. The direction is that the rest of the cast are to stand motionless: time is frozen; we are a stationary relief to the struggle deep within Hamlet. They only problem is that standing stock-still for the minutes it takes for Mr Stephens to deliver the speech is beyond me - I want to blink, I want to sneeze, most of all I need to move. There a four positions for the Switzers in this scene. There are two standing behind the King and Queen. Another Switzer stands guard at the back of the stage. Then later in the scene, a Switzer makes an entrance to Ophelia’s rear as she sits with Hamlet opposite the throne. Each position presents a different perspective of this key scene.

We walk on stage. To my right, a fellow Switzer stands behind Polonius. To my left, Neil (the Switzer Leader) stands behind the Queen. I am behind the King. I relax and start to watch the action develop. I notice out of the corner of my eye that Neil is looking at me strangely. The “play within the play” continues and the on-stage tension is intense when Neil leans over to me and whispers - “the throne!” Suddenly I remember. In the next thirty seconds, as the King rises the throne is meant to crash behind him. Unfortunately, I’m now standing in its way. I start to back slowly away from the King only to bump-up against the stage wall. There is nowhere for me to move. I glance at the chair. It looks pretty substantial and I really don’t want it to crash onto my toes. I have no idea what to do and the climax of the scene is imminent. We are now meant to be standing still with “time frozen”: Mr Stephens will whip out his dagger, the King will rise, and my toes will break. Inspiration strikes. Standing motionless I pivot on my heels and splay my toes out. I may look like a mediaeval “Charlie Chaplin” but when the throne crashes down it just misses me: “Toe be, or not toe be” Standing behind the Queen is much safer (no crashing furniture) but it presents its own challenges. When the King stands and chaos ensues, the Royal party is to be escorted to safety down the parados and through the auditorium. Unfortunately, there is a bottle-neck on stage as eight people try all at once to get onto the narrow gangway. Gavin sorts out the choreography and the Switzer is asked to “go just behind the Queen”. This is easier said than done. Her Majesty is wearing a dress with a long train and there is a real danger of stepping on it as we all charge out of the theatre. Whenever, I stand in this position I worry about catching the train and the dress coming-off - as in a bad farce a la “Carry-on-Gertrude.” The easiest position is to stand at the back of the stage with the rest of the “Players”. The wide doors give everybody room to get off. My only problem occurs when one of the cast has a bad-back. She is going slowly off-stage and I try to give her room. This is great for the two of us but it causes a traffic jam on-stage. As actors mill behind me, I turn into a “Switzer Sandwich” between an immovable object and an irresistible force. This philosophical problem is solved when one of the more “experienced members” of the RSC shoves me in the back off-stage. The last (and my favourite position) in this scene is to walk out behind Ophelia to confront Hamlet. Ophelia is seated opposite the Royal party on stage right. Hamlet is beside her. He taunts and provokes the King. When our cue is given, I open the door and walk out towards Hamlet. As I walk, Hamlet is surrounded by Switzers. He turns to face me with a sneer of contempt.

No-one – no-one – gets this view of the play. It is the pivotal point of the production. There are over 1400 people watching this but only you are looking into the eyes of Hamlet and seeing his reaction to the King’s action. Toby Stephens is a superb actor and I have no doubt that if a stage-hand had thrown a sack of potatoes on stage instead of a Switzer, he would display the same emotions and reaction. But for the few seconds when I walk on stage and hold Hamlet’s attention I think: this is Shakespeare’s greatest play, set on Britain’s best known stage and you are watching one of its finest actors. It is a fantastic moment. The temperature is rising, the King talks of fear and rage. We walk left, right and centre swiftly across the stage. In the Stratford run, this was the first scene immediately after the interval. King Claudius, his courtiers and all four Switzers burst through the centre-stage doors as a bell tolls loudly. Our brief is to search the stage quickly and then walkoff purposefully – like American Secret Service men “securing the perimeter” for their President.

We are on stage for all of three seconds but I always enjoy this scene. I charge across the stage and then straight down the parados. My eye fixed always on the poor occupant of the aisle seat in row G. I like to think of someone settling into their seat after eating a relaxing ice-cream during the interval. They are looking forward to the rest of the play when suddenly a man in chain-mail and leather boots with his hand on a sword is rushing towards them. It’s childish but fun. As the Switzers leave, King Claudius is left alone on the stage. "Oh, my Offence is rank". The King for the first time faces the enormity of his crimes: the murder of his brother, the theft of both his brother’s crown and wife. In repentance, Claudius falls to his knees in prayer. As he prays, he is joined unseen by Hamlet who decides that, whilst Claudius is in this state of grace, he cannot be revenged and stab the murderer King. I am watching the performance from the stage-right wings, I’m aware that Toby Stephens is standing at the adjacent entrance. Suddenly he sprints away back towards the prop room. His cue is seconds away and there is a real danger that he will miss his entrance. The King is going to be stuck on his knees. If Toby does not turn-up promptly then Claudius may even find divine forgiveness. That would likely spoil the rest of the play but we would get to the pub quicker. Just in time, Mr Stephens returns. He places his forgotten dagger in its sheaf whilst wearing a rueful smile. “Toby, or not Toby.” “Oh, my Offence is rank”. One of the Switzers has farted as we are crowded backstage waiting to make our post-interval entrance. The cue-light has turned red in preparation of our entrance so there is no escape. Four people hold their breaths desperate for the green light to release them on-stage. The bell tolls, the doors are flung open and I charge towards the occupant of the aisle seat of Row G.

The Prince is under pressure, though not quite “on the lam” yet.

A search-party enters and goes chasing after Hamlet.

Eventually, we draw our swords and chase Hamlet offstage along the parados: I really did not enjoy that scene. The King asks “Where’s the body?” Hamlet is loath to tell him. We’re told “Go search the lobby, quickly before you smell him.” The action is speeding-up. More and more doors are left open on stage as the play develops. This may be a deliberate action by the Stage Designer: the open doors no doubt illustrate Elsinore crumbling as the King fights to keep control. However the only problem is that when the doors are open it is impossible to move off-stage without being seen by the audience. Consequently, we need to be in position early or risk not being able to reach our entrance. This is difficult for the Switzers but even more of a challenge for the King. In the preceding scene, he must talk with the Queen, exit stage left and then sprint to the main-doors at the back before the “Arrest” scene opens the four doors. He has about eight seconds to do this. As he gets there, he joins an un-regal jam consisting of Fortinbras, a stage-hand, a Switzer and himself. All are trying desperately to hide behind a narrow piece of set.

Fortinbras makes his entrance, back-lit none can see your face.

Though make sure in the tea-break your helmet’s in its place

This scene runs straight-on from the Interrogation. Hamlet is despatched to England and the Switzers are to instantly change into Fortinbras’ Norwegian army. The theatrical “sleight-of-hand” is achieved by judicious use of back-lighting and wide helmets. During the interval we place our helmets to hand by the side of each of the four doors. The only problem is that with the wide-open doors from the Arrest, three of us can’t get into position without been seen by the audience. In the end, only the Switzer on stage left is in position to support Fortinbras. Hamlet may talk of “the imminent death of twenty thousand men” but for that preview night only one of the b*****s turned-up. When we do eventually get it right, a strange thing happens. Because we are back-lit when standing in the doorway, I can actually see the audience. It is an intimidating sight. I’m assured by the Stage Manager that none of the audience can see us – and one night I even test this by sticking my tongue out at the crowd – but even so it is a disquieting sight to have 1400 people looking directly at you.

One evening, we are told that Kate Winslet and Sam Mendes are in the audience. The front-left of the balcony is mentioned as the likely spot to see them. As the lights behind us illuminate the audience, I try to pick them out but with no success. “Who’s for King Laertes?” the blooded unruly mob roar. As we walk shouting to the stage, then hang around by the door. There is rebellion in the ranks. The play needs a crowd to storm the Castle. Laertes is thirsting to revenge his father’s death. The problem is that a few Switzers does not a riotous mob make. The solution is to heavily disguise some of the leading actors who have been dead and/or hanging around the Green Room to boost our numbers. "Bah, five years at Drama College and all I get to play is the crowd scene". The “cream of the Company” wraps scarves around their faces and place helmets low on their heads. We Switzers thoroughly enjoy this as we make free with the fake blood and charcoal-grime. “Do you do nosebleeds?” I ask the make-up assistant. “it can be arranged” is the obvious reply. We form our “mob” right at the back of the Theatre. We are to scream and shout to represent the riotous crowd.

Laertes, returned from distant France (or in reality his near-by digs), is bouncing up and down. He psyches himself into the part. We search for any spare weapons that the prop department may have left lying around. I select a likely looking cudgel from the “Macbeth” production and we are ready to go as our cue is given- “off-stage noise … go”. We march towards the stage shouting "Laertes for King …. Who's for King Laertes? …. For King Laertes". We enjoy the serendipity of being able to scream “For King” at the top of our voices to 1400 people. As we reach the stage, we burst through the centre doors. Several times, the crowd at the back are too over-enthusiastic and one of our group tumbles forward onto the stage. After that, the pressing “mob” disperses leaving a hard-core of disguised Switzers to act as the rabble at the door. We are chaperoned by Ian Drysdale, one of the actors, who puts up with our nervous chatter with good grace. Ophelia and her ladies join this depleted group behind the centre-stage doors. They are about to take the stage. Everyone is upbeat and enjoying themselves, silly jokes are quietly made. I look at Ophelia when suddenly her face dissolves into abject misery.

God, what is this? stage fright? is she still going to be able to go-on? I’m still wondering what is happening when the door opens and Ophelia goes on stage to perform her “mad scene”. A lesson is learnt about actors, their ability to turn on emotion at will. The funeral party enter, walking slowly in a column. Her brother gets a bit upset – wants it to be more solemn. The finishing-line is in sight. It’s a long play (over three hours) but the actors play the text with verve and urgency. In the preview, this scene used all four of the Switzers. Two are to enter from the back of the theatre escorting the funeral party along the parados. The other two are placed at the back of stage. They are to appear on the parapet of the set. Two silent guards watching as the Royal party takes its place. To reach up to this part of the scenery, we climb a narrow ladder and then balance precariously on a “telephone-directory” sized platform. Ten feet in the air, no visible means of support except a handle at groin level. We emerge from the backstage gloom, and face directly into the blinding stage lights.

The direction is simple: “slowly, casually remove the crossbow from your right-shoulder when Hamlet reveals himself. No panic, but a gentle ratchet of the tension.” The action is impossible: I’m sorry Mr Boyd but no-way am I letting go of this handle and groping around for my cross-bow. There is the distinct probability of me unbalancing and then plunging to the ground. Not only would that involve me breaking a leg (at best!) but it would also look pretty lousy from out front. The audience would be treated to the view of one Switzer disappearing like a coconut knocked from a fairground shy. Half of them would then spend the rest of the scene wondering if they win a teddy-bear when the second Switzer falls away! All in all, it's a difficult position to play and I’m glad when it is eventually dropped Meanwhile the rest of the Funeral party forms in the corridor alongside the auditorium before entering at the back of the theatre. It is hot and people are flaked out. The funeral bier is at the front. Occasionally a member of the audience is caught sneaking out of the auditorium early like a truant. They realise in shock that we are all assembled in the corridor. As a theatrical joke, Ophelia and the murdered King play the gravediggers in the preceding scene. Christine, the Assistant Stage Manager, lies down on the empty funeral litter for a rest. Ophelia, fresh from sexton-duty, joins us and lies down on top of Christine: “hmmm, girlon- girl” is the kinky comment. “hmmm, “dead-girl”-ongirl” is the kinkier riposte. “When do the points lapse for speeding?” A stockyfigure with a broadsword strapped across his back, and fierce dagger strapped to his side is looking at me expectantly. This is surreal, A Switzer is a man of the world but does his knowledge stretch to the penalty system for motoring offences. I mutter that I’m not really sure. “But they do lapse, don’t they?” He then picks up on my confusion “You are a policeman aren’t you?” I realise that he’s confused me with another Switzer and I confess my lack of knowledge. We rehearse the funeral scene. I am standing at the back of the stage with the brief to keep a constant distance between myself and the King. The only problem is that he keeps moving about. First walking forward, then retreating and finally walking forward again. As I am trying to keep pace with him I'm reminded of the "Hokey Cokey". The Director manages to restore order to the situation, "You at the back, try not to move about so much … in fact … try not to move at all". It's okay Mr Boyd, I can take a direction and I resolve to stand still for the rest of the rehearsal.

The Queen lays down her flowers, Ophelia is interred.

Hamlet fights Laertes whilst Horatio is deterred.

The Prince has gone and torn it, he’s really made a scene.

The King now wants him followed, so go off before the Queen.

Tricky. The Queen is appalled that Hamlet has desecrated Ophelia’s funeral and further shocked that the King now wants her to follow her son. She needs time to register her concern but as the King’s man, I am meant to move instantly upon his order. My brief is to wait for the Queen to obey the King, and then follow Hamlet. Unfortunately, wires are crossed and her brief is to follow me out. We stand on stage looking at each other. I’m confused. I made a half-step on the cue line but no-one else “went”. Had I misheard (probably) or was I just at completely the wrong part of the play (equally likely). It would be lese majesty of the grandest order to walk off by myself. I’m wondering where this scene is going (no doubt along with the cast and the 1400 people in the audience) when the Queen takes the scene in hand and marches down the parados.

Hamlet (dying) kills the King who tried so hard to “top him.”

We walk on stage, pick-up the Prince. For God’s sake do not drop him!

Lifting Toby Stephens is proving to be a major task. My wife is a Physiotherapist and is adamant that the scene should go. I point out that Mr Boyd is unlikely to change the ending based on the views of the Switzers and ask “How would you lift him in a hospital” “We wouldn’t, we would use a hoist”. A true answer but not particularly helpful or practical for a play set in mediaeval Denmark. Hamlet and Laertes take part in a spectacular duel. Hamlet has been on stage for coming up to three hours; He has met ghosts, organised plays and generally run around. Laertes is fresh from his cup of tea. Yet both actors manage an intense five-minute fight. The cast shies nervously away from their frantic sword-play. They look like figures from an Egyptian frieze as they press themselves back against the wall of the set. It is the night of the first preview. The cast has performed magnificently and the audience has responded well to the production. All that remains is for the Switzers to march on-stage and then lift Hamlet’s body onto their shoulders. I am the lead Switzer and I march confidently on stage towards the Prince’s corpse.

Unfortunately, as I do so Fortinbras launches himself downstage towards the audience. There is an imminent train-smash until the Norwegian manages a deft sidestep to go round me. Afterwards, the actor (understandably) berates me for getting in his way. I don’t mind this as it was my fault but I notice as he calms down his accent is becoming more and more Welsh until he asks plaintively; “Oh, am I being a bit arsey about this?” What is worse though, on stage that night, Mr Stephen’s arm catches the front of my helmet and knocks it over my face – s**t ! Unfortunately some in the audience titter. This scene needs to go. The final scene, a costume change, now a Norwegian soldier; stand smartly in the door-way, a crossbow on your shoulder. “We’ve changed the ending …” says Gavin. It’s the third preview night and still we meet on the stage an hour before the “half” is called. We are getting better but still need to get the entrances and exits clear in our minds. “… We feel we need to focus on the relationship between Hamlet and Horatio.” concludes Gavin. Now, I’m all for re-interpreting Shakespeare but changing the ending does seem a touch radical. What happens now; does Hamlet live? Does he marry Horatio and live happily ever after?

In effect, the only change is to drop the Switzers carrying Hamlet off-stage (hurrah!). Now, Horatio cradles the dead Prince as the stage-lights slowly fade to black. We are to stand in the doorway acting as Norwegian soldiers in support of the newly arrived Fortinbras. As the cast stand silently, there is the sound effect of a sword drawn across a stone floor. I think it is meant to evoke the memory of the Ghost of Hamlet’s father but in truth it reminds me only of a mediaeval “Ernie” rattling his milk bottles in his crate. A final peal of ordnance makes the front row jump. And that is it, the play is over once again and “the rest is silence”.

The play is done and dusted, and we made it with some luck.

So go enjoy the curtain call, then go down the “Dirty Duck”.

Still, it’s a fair reflection of how I feel. Toby Stephens is taking a well deserved ovation for his portrayal of Hamlet: his teenage fan-club must be in though as a series of high-pitched screams are heard. Hiding behind the set, two of the cast start to mime The Beatles circa 1963 (guitars under the shoulder):” She loves you, yeah, yeah”. Other nights are more restrained: “Well this applause is mooted” “Don’t you mean muted?” “No mooted: they’re discussing whether to clap” One quiet Thursday matinee performance in the dogdays of August is enlivened only by noticing that one of the audience has fallen asleep in the third-row. Fair enough, it is a hot day and the auditorium is stifling

however catching a quick snooze does seem a bit much. We resolve to march loudly down the parados in an effort to wake the guilty party.

The Royal Shakespeare Theatre is located on the banks of the River Avon. The famous pub “The Dirty Duck” (real name “The Black Swan”) is two minutes walk from the stage door. After the show, the actors and the audience mix democratically for a late-night drink. As this is England (where “ye olde worlde” customs rule), the last order for alcohol to be served is 11 pm. The play finishes ten minutes before time is called and consequently there is a desperate crush of theatregoers at the bar. Less democratically, flashing your RSC staff card discreetly at the bar staff gets you served quicker. Gavin and the Murderer Player King are standing by the bar; two untouched pints of beer in front of them. They are deep in conversation trying to unravel a problem in the “dumb-show”. Here the Player King mimes the murder of Hamlet’s father. The production prides itself on keeping the action taut - exits and entrances overlap as the audience is driven towards the play’s bloody conclusion. However the silent minutes of the dumbshow slow this tempo down. The duo contemplate approaches to keep the action flowing. Their solution: introduce humour, but how?

Inspiration strikes Gavin. He places his finger into his mouth, puffs out his cheek and then flicks out his finger with an audible “POP”. The Player King eyes him suspiciously. “Do this when you remove the cork from the bottle of poison. It’ll be bound to get a laugh.” The Player King is unsure that the audience will be able to hear the noise in the vast auditorium. The couple start to experiment, trying to get the loudest “POP” possible. Each in turn places a finger into the mouth and flicks it out with varying degrees of sound. Across the bar, a Japanese tourist stands watching unsure and transfixed at what seems to be a curious mating ritual. In a pub a long way from Japan, it is a strange case of “ye olde worlde” behaviour to tell the folks back home about.

The Stratford Run is over, all say “it was a hit, Sirs!

The cast were all on top form and what about those Switzers!”

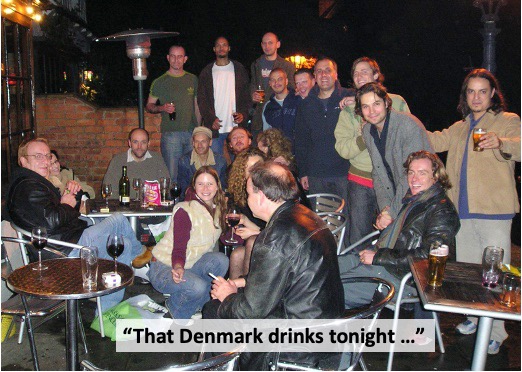

In November 2004, the RSC announce that they have eliminated their deficit and are back on an even financial keel. This is a turnaround of £8m and an extraordinarily disciplined feat. The same day I receive a letter bearing the RSC logo. It is from Mr Boyd saying thank-you for our work over the summer. I look closely at the envelope and realise that the stamp has been reused. A small saving but then if you "look after the pennies …." Switzers-reunited: The eight Switzers all meet-up again in the "Dirty Duck" for a drink just before Christmas. The team that went to Newcastle share the gossip and adventures of the wild North. It's a quiet night in the pub and we sit around the table in a window alcove. It's dark and cosy with the fire lit. At around nine o'clock a noisy group of actors burst into the bar; it's the cast of "Beauty & the Beast". This is the RSC’s Christmas show and it has a welcome early finish. We watch them jealous of their excitement; the buzz of coming offstage and then relaxing in the bar. We remember the hanging-around, the illusion of glamour, the use of "sleight of hand" and suspension of belief to create the magic of theatre. "Hey, it's snowing", we look out of the window to see flakes tumbling to the ground. It is a picture-postcard ending to our evening. Just as suddenly the snow stops. It is actually coming from a snow-machine on the first-floor of the pub. It is blowing fake snowflakes onto the front beer-garden. We all laugh: the illusion of glamour, the creation of magic...

Exeunt Switzers

Epilogue – “Cast thy nighted colour off.”

"Are you sure this is a good idea? Do you know what this play is about?" asked my wife. Of course I knew what Hamlet was about; written by Shakespeare, set in Denmark, involves a skull and an indecisive Prince. The fact that my mother had died a few weeks previously seemed irrelevant when I answered the advert in the local paper to be an extra in the Royal Shakespeare Company's production. Her death had upset me greatly and I wanted to do something different to mark that summer. I had never been on stage before and I felt that it would be a great experience and something to tell our new-born daughter when she grew-up. However what I was about to learn was that my wife was right and this was in fact a play all about Death; its impact, its ritual and its consequences. Ghosts appear and trouble the living, murders are committed, dead bodies are hidden, suicides are denied proper burial, men fight in uncovered graves and in the final scene the body-count rises to "a sight more accustomed to the field." This is not the ideal play for someone struggling to cope with grief. In one funeral scene, I had felt my eyes fill with tears as Ophelia’s corpse was brought on stage.

This gained admiring glances from the actor next to me – “he’s really getting into it” – but it didn’t make me feel any better. Some Shakespearian scholars believe that Hamlet is the playwright’s response to the pain caused by a change in Christian funeral rites. The loss of Purgatory – “I am forbid to tell the secrets of my prison house” – causes Shakespeare to contemplate Death and the customs we use to cope with it. I had spoken to my mother on the telephone about my being part of the play. Her last words to me were “tell me all about it when I see you at the weekend”. She died the next day. I was alone, about to go on stage and challenge Hamlet in my favourite “Players” scene. In the corner of my eye, I could see a chair (perhaps a throne) from the Macbeth production propped up against the wall. I became aware of a thought. Not a ghostly presence or a visitation from the “undiscovered country” but instead a shared image. Of the two of us; laughing and joking at the absurdity of my doing this. Merely a simple sense of a person loved. The memories of time shared and the realisation that these are the substantial forms that can be held onto. They are not lost to Death. Through the wall, I could hear Hamlet taunting Ophelia. The cue light turned from red to green, I opened the door and stepped onto the brightly-lit stage.

If you have enjoyed reading about "The Switzer's Guide to Hamlet" and would like to support this web-site, please use the button below to make a donation to support its running costs.

Many Thanks, Darran